This online exhibition will be on view until December 2025

For many people of colour living in communities with a white predominance, the question Where are you from? is a regular encounter. While this question might be considered harmless, it can be othering and tiresome to constantly explain your existence.

Where are you from? was created to celebrate, educate and raise awareness about the BIPOC identity, through thought provoking art and storytelling.

Therapy for some, an education for others; the project stimulates the vital conversations about belonging and acceptance that need to be heard and shared.

.

In this exhibition, curator and writer Sabina McKenna brings the Where are you from? project to UNSW. Students and staff share personal stories of what it is like to experience this question in a mostly white Australia. Together, these stories unpack the different connotations the question can carry and shine a light on the complex relationship between nationality, ethnicity and personal identity.

Since its inception in 2018 Where are you from? has gained national recognition. After being launched at Blak Dot Gallery, Melbourne, and later shown at Goodspace Gallery, Sydney, the project has been featured by media throughout Australia including ABC, Sydney Morning Herald, Vice, Frankie Magazine and FBI Radio.

Hover over each portrait to read the stories.

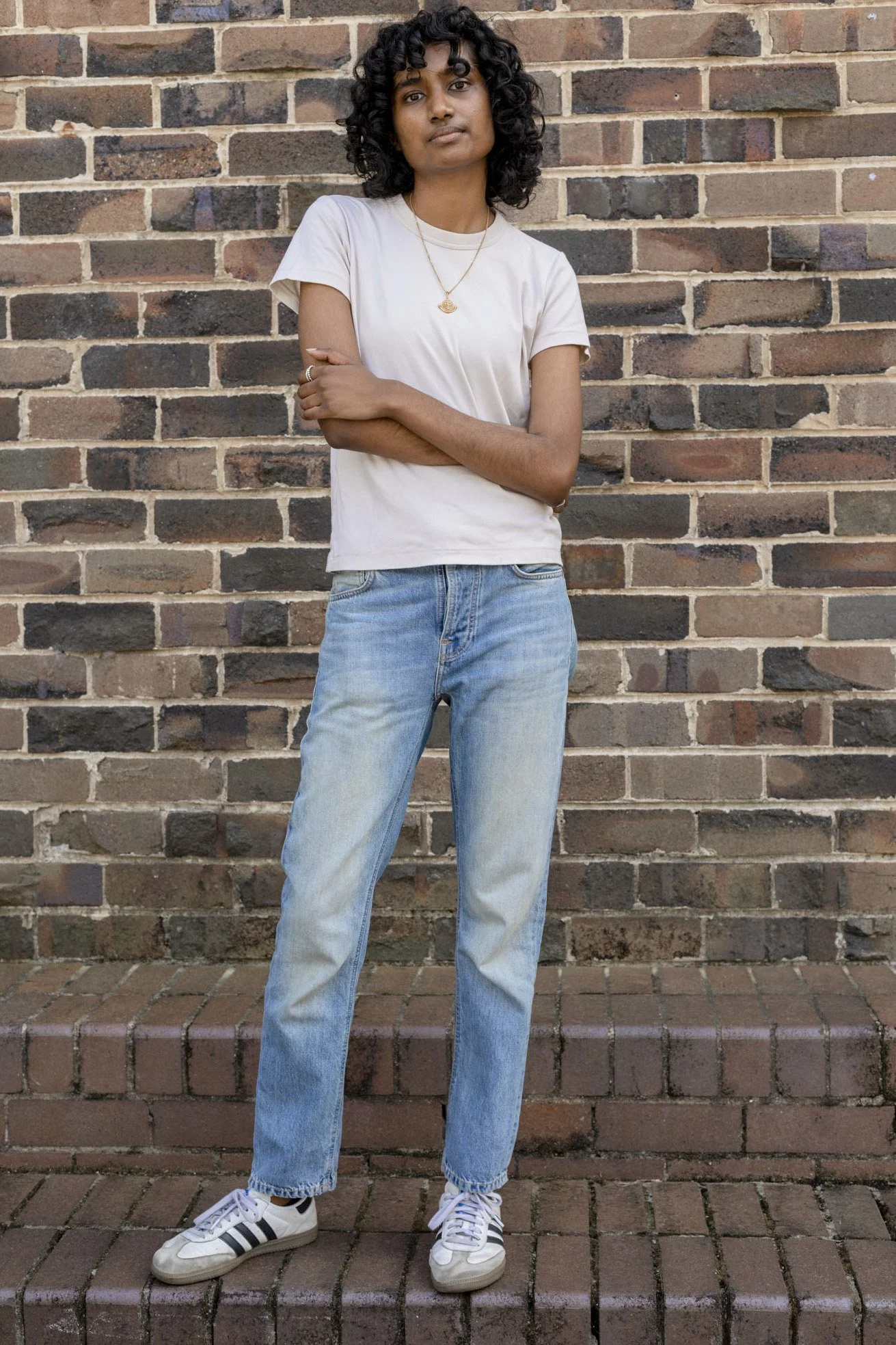

Farhana Laffernis | Clever things that I should have said

Context is everything. Within that question there’s curiosity at best - and hostility at worst - especially when it’s asked by a white person. There’s no safety with it. But it’s different with people of colour. In our own spaces, that same question can show solidarity and respect. I often find myself actually wanting to answer and to spare no detail.

I remember being asked where I am from when I was a student and working in a cafe. I told her my family are migrants from India, and that we came here when I was six months old. She replied: ‘You speak very good English’. She thought that was a compliment, and I think I may have even thanked her. As with all vaguely racist interactions, I spent hours going over it in my head thinking of snappy comebacks and clever things that I should have said.

The last time I was asked, I answered that I am from Sydney. Now when I’m pushed for more details I go granular—region, suburb; not country. Sometimes they get it and stop asking. Sometimes they are visibly dissatisfied with the lack of my explanation to justify my being Brown.

I’m still learning that no matter what answer I give, it is enough.

Roshana Sultan | The Brownies, The White Immigrants and the True Blue Aussies

I have lost count of the number of times I have been asked this question.

How I feel at the end of such an exchange largely depends on who has asked the question and I tend to put these people into three groups. The first are ‘The Brownies’: the new migrants, or second or third generation people who, like me, are not white. In this context, I am likely to be direct about my cultural background as I can see that what they are hoping to find is a connection. Am I also from their home country? Or, failing that, is my background close enough to theirs that I may share an understanding anyway?

Then there are the other two groups, who tend to get under my skin… the exchange usually goes something along the lines of this:

Q: ‘Where are you from?’

A: ‘Wollongong.’

Q: ‘What about your parents?’

A: ‘Oh, they are still in Wollongong.’

Q: ‘Where are you/your parents originally from?’ or ‘Where are you really from?’

A: ‘Apparently Adam’s rib.’

I reserve these responses for ‘The White Immigrants’ – the Europeans, New Zealanders, White Africans and the like. The people with an accent, but who can make me, a person born in Australia, somehow feel less ‘Australian’ than them. These encounters often end with a comment on how good my English is.

Then there’s the final category: ‘The True-blue Aussies’. Those who ask ‘out of curiosity’ but with just a hint of unintentional casual racism. Those that when they finally get their desired answer - usually after far more questions than they intended to have to ask - will follow up with something along the lines of: Wow, you sound occa as!

While nobody in the two ‘white’ groups mentioned above has ever asked to touch my skin, which happened often when I used to work in North Carolina, encounters with both serve as a stark reminder that no matter how ‘Australian’ I might feel or sound, it’s how you look that matters - at least as far as first impressions go.

Never has this felt more concrete than on my first day at my new job, when the office receptionist remarked, ‘Well, I suppose you look the way I would expect you to look from your name, but you certainly don’t sound like it’.

And on another day - that was by far my funniest experience, that highlighted just how much the way I look impacts the way I am perceived - when I met a friend’s father-in-law who assumed my English was probably not great. He introduced himself by tapping his chest and saying in a slow steady voice: ‘My name, David’. Confused by his gesture, I mistakenly thought he might have been hearing impaired, so I responded in exactly the same way. We continued to talk for several minutes in the same style – broken English and exaggerated gestures, before my friend came over and whispered, ‘What the hell are you doing?’

‘You didn’t tell me David was hearing impaired’, I responded. To which dear old David replied, red-faced and apologetic: ‘Oh gosh, I’m not, but apparently I might be a bit of a bigot. Sorry.’

Cheyenne Bardos | An identity always up for debate and discussion

I was seven when I moved to Australia from Manila. I was young enough to not realise the nuance behind a microaggression, but old enough to feel othered whenever someone asked me the question: Where are you from?

By the tender age of twelve I had learnt to expect that the question was always coming. I could see it in their eyes—they could feel it on the tip of their tongues, and twenty seconds into a conversation - the words itching to burst out, to quell their curiosity - they would say it… I knew exactly how it would start:

What are you?

Where are your parents from?

What’s your, like, original country?

In the case of an older white women who once came into the jewellery store that I worked at:

‘OHHHH look at YOU! You are so beautiful! You are so gorgeous. Louise, come here! Look at her, look how gorgeous – sweetheart, where are you from?’, she started.

‘Are you Vietnamese/ Chinese / Japanese / Thai? Oh Louise, she’s Phillipine like Lucy! I was going to say, you look like this beautiful actress – I forgot her name… I don’t know if she is Phillipine. Ugh, you know who she is, but I’ve forgotten her name! It’s SO hard to say— I don’t want to butcher it. But, Oh your kind are SO beautiful. Just stunning!’

I do love compliments, but the whole encounter made me feel like a zoo animal. I remember thinking: why do people always have to tell me that I look like someone else? Is it because they can’t tell the difference between East Asian countries? I was fifteen when this happened.

In the case of older white men; I served many of them at the ice cream shop I worked at when I was thirteen…

‘Where are you from, sweetheart?’, they’d ask.

‘Oh, the Philippines? I knew it! My wife/friend’s wife/girlfriend is from the Philippines - you remind me of her.’

In the case of the other teenage girls I’d meet at parties, the conversation would continue:

‘Where are you from?

Oh, not China?

I thought you were Chinese because you look exactly like [this person I know] Alice!

What’s the Philippians?

Oh, you’re so pretty, I would’ve never guessed it.

I love Asians, I’m so jealous of your tan.’

In the case of a Filipino woman, who I met when I returned home to Manila:

‘Where are you from?

Ahhhh, Australia. I could tell that you didn’t grow up here.

Can you still speak Tagalog?’

‘No, I can’t speak it fluently anymore’, I replied. But I can still understand it, and read it. My parents never really spoke to me in Tagalog when we moved to Australia, and so I thought it was embarrassing and didn’t want to speak anything other than English so I stopped speaking my mother tongue. Now I regret it and you can tell when I try to speak Tagalog—it just doesn’t sound right.

Of course, I didn’t tell her all of that. I thought nobody in the Philippines would even have to ask. I look like them, right? I may sound different, but I look exactly the same: we have the same nose. We have the same complexion. We have the same thick, jet-black hair. So why do you still assume that I’m different? Why can’t I belong with you, too?

I thought that it’d all slow to a halt the moment I moved to Sydney from regional NSW. I remember feeling so excited to finally be in a metropolitan city with other diverse people. To be surrounded by accents and languages and melanin. But they asked me in one of my first uni classes. They could tell that I wasn’t Filipino-Filipino; in fact, I was actually ‘whitewashed’.

‘Oh, you’re from Wagga! That makes sense, you must have moved there when you were really young. What was that like?’

Being asked the question ‘Where are you from?’ immediately instils a deep sense of exclusion in me. It feels strange, because at the same time I am overcome with a deep sense of pride when I answer. I know that people are just curious, but this curiosity has led me to believe that I am ‘the other’ first and myself second. I will never be the default idea of a Filipino or an Australian. I will always be ogled at for my ethnicity before I say my name.

I understand the inherently human instinct to classify and categorise everyone we meet. I understand that most people don’t mean to offend me. I understand that I am, at times, deeply sensitive. I understand that the question brings the opportunity to talk about my country, my grandparents, my culture, my food; how my Dad moved to Wagga for three months where he lived alone in a motel room and washed dishes so he could buy a house before Mum, Inigo, and I flew in.

And at twenty-three, I certainly keep all of those things in mind when this question is approached – but I’m not always in the mood to explain my entire life story to a stranger. A stranger who will eat it up with every last bite, because to them it’s an ‘exotic’ story of perseverance and resilience. It’s how they make sense of immigrants like me. It’s a reminder of how my identity will always be up for their debate and discussion.

Eva Zheng | A question I hoped people would ask in a different way *Rethink this title

Last Saturday, at a farewell party for one of my friends, a young woman wearing a white t-shirt and black glasses approached me. She started a conversation and shared that she was also from UNSW.

‘Hi, where are you from?’, she asked.

‘Oh, I'm from China,’ I said. I could feel she didn't mean anything bad when she asked that question, but despite that I felt a bit uncomfortable. I wasn’t sure why I felt that way until she smiled and said: ‘I thought you were from Japan’. I awkwardly smiled back and stopped the conversation.

Later on after I got home, I started thinking about why I don’t like being asked that question. Although it might have been asked out of curiosity, and in an innocent way, it triggered something very personal for me; for my sense of belonging.

As an international student, I’ve been living in Australia for almost four years. I have been trying hard to get used to the way people talk and behave here by getting involved in the community, but I still feel like I don’t belong here - which is sad. For this kind of question, I hope people ask in a different way.

Maybe one day I'll say it | Geirthana Nandakumaran

I often get asked where I'm from in professional settings. In most social situations, I find it quite normal for people to ask as I think it helps whoever I'm talking to understand me better. But professionally, I find it quite uncomfortable. How does knowing my ethnicity help me do my job? So they can tell me if they've ever visited Sri Lanka and how beautiful it is? I've been there only twice in my life, and on top of that my family fled the country due to ethnic persecution that still isn't recognised on a global scale.

The trauma of having to continually justify my identity is draining and I'm yet to figure out how to navigate the question; I usually just tell them my parents are from Sri Lanka and that I was born and raised in Sydney. I often come away from this response with self hatred for not saying what I was thinking, but maybe one day I'll say it.

Cindy Lemes | We Brazilians have many different looks.

I’m originally from Brazil, a country with more than 210 million people. The state I was born in is the most densely populated, and the greater Sao Paulo has more than 20 million people - nearly the entire Australian population. We, Brazilians, have many different looks. We come in different shapes and forms and can be from the most diverse ethnic backgrounds. When I left Brazil, 16 years ago, I barely spoke English.

I first went to the U.S., where I expected I would be asked where I am from. While there I even had to re-learn how to pronounce my name ‘correctly’ in English, but I was ok with that.

I recall my first week in the United States: there were four or five of us Brazilians, among people of other nationalities. One girl (I think she was German or Swedish) was so surprised that one of the Brazilians in our group had fair skin and green eyes. I guess she expected we would all look similar, with tanned skin, brunette hair, and the knowledge of how to ‘Samba.’ That was a big mistake, and pure ignorance. We didn’t expect her to know about our country or our culture, so we happily told her how diverse our country is, and then we moved on. No hard feelings. No dramas.

After a few years of living in the U.S., I had told people numerous times that I am from Brazil. Then I arrived in Australia. I spoke fluent English, but with a slight American accent and oh did that make some people stare. But did it bother me? Not at all. I was amused. Like most people, I am very curious. I too had asked other people ‘Where are you from?’ Or better yet, ‘What is your background/ ethnicity/ heritage?’ I didn’t ask to judge people in any way, but because I am curious and eager to learn about their culture, their customs and their beliefs. I think people and their stories can be fascinating!

That being said, I do believe there can be an appropriate time, place and tone of voice that can make for a better way of asking the question. If I am asked with a tone of voice that’s not to my liking, I probably won’t engage in the conversation. I may simply answer: ‘I’m from around here, period’ and move on. But most of the time I have an open-mind and an open-heart toward that question. I like to assume it comes from a good and curious place. And I’m happy to let people know that I am a proud Brazilian-Australian – and to sometimes have a lengthy and enjoyable conversation about Brazil!

Sanjay Alapakkam | Home is where your heart is

‘Where are you from?’

It’s the question that permeates every facet of my experience: workplaces, classrooms, meetings, parties, dates…

How do I feel about it?

Now that’s a difficult question.

I was born in India, moved here when I was 7, and the world has changed dramatically over this time. The Sydney of 2006 is not the same as the Sydney of today. And yet, after all this time, in which I had become a citizen engaged in my community, the answer still rolls off my tongue:

‘I’m from Chennai, India’.

If I hadn’t given that answer, the conversation would go something like this…

‘Where are you from?’

‘South Sydney’

‘I meant, what’s your nationality?’ or ‘Where are you really from?’

‘Indian’

I say that knowing my Indian citizenship had to be relinquished when I accessed my Australian citizenship.

I say that knowing that ‘nationality’ technically refers to citizenship and not ethnicity. But if nationality is what they want to know, and being from Sydney isn’t the ‘right’ answer, is my citizenship not ‘really’ Australian?

Now that’s a difficult question.

What I know is citizenship entitles you to be a member of Australia.

Its values are my values.

Its natural landscape is there for me to appreciate and respect.

Its place in the world is for me to be proud of.

Home is where your heart is – it is your place of return.

My Australia is where I’m from.

Priya Pandarinathan | An opportunity to share my cultural identity

I was born and grew up in India, but I’ve been living in Australia for over ten years now. On many occasions I’ve been asked: ‘Are you from India or Sri Lanka?’, rather than ‘Where are you from? People assume I’m definitely from either one of the two countries based on my physical appearance. I’ve also heard: your English is even good, no Indian accent’. I used to wonder if white/fair skinned-Indians also get these kinds of questions as frequently as I do. At times I have sensed that people might be associating someone’s knowledge and character to their skin colour. In the region of India where I grew up, there is a saying: A white man never lies.

One day I attended a community kids playgroup, with my children. The moderator started the conversation with the kids by asking them to introduce themselves with their ‘name, how old are you and where are you from?’. It was a casual request, but my almost 5-year-old kid answered with the suburb we live in and then looked at me with uncertainty.

I am sure many people get this question at work-related events, or national/international conferences as an Icebreaker. But whatever the intention of the person asking the question may be, I will usually always answer where I was born and where I live now. If the question is asked with respect, I see it as an opportunity to share my cultural identity. But if it was asked with a racist attitude, I simply ask the question back.

Ketao Zhang | “你是哪里人啊?”

Middle school, China. I was known as the kid with a funny accent from a different town. ‘Where are you from’ was a friendly question for fellow classmates to start a conversation with me. Back then, I loved hearing it because it meant that I was making a new friend.

‘Where are you from, dude?’

High school, West Virginia, USA. At sports events students from other high schools asked me this. It was surprising at first - how did they all know I wasn’t from here before I even revealed my accent? It didn’t take long for me to realise that compared to everyone else in town, I looked and dressed differently. Sure, the question might have been asked simply out of curiosity, but I wasn’t so happy about it anymore - it only served to remind me that I am different to everyone else.

‘Where are you from, mate?’

In Australia, I hear this question most often in the hospital when I’m taking patient histories as a medical student. At first, I was a bit uncomfortable sharing my story with just anyone. But I realised that patients asking this question meant no harm - they intended to build a friendly rapport with me as an individual instead of a remaining total stranger under a cold surgical mask.

The people around me are from all around the world and so I have been open-minded to embracing diversity. Whenever people ask me where I am from, I always answer happily and proudly: ‘I’m from Hunan, China, lived in West Virginia, U.S., and now I live in Sydney Australia.

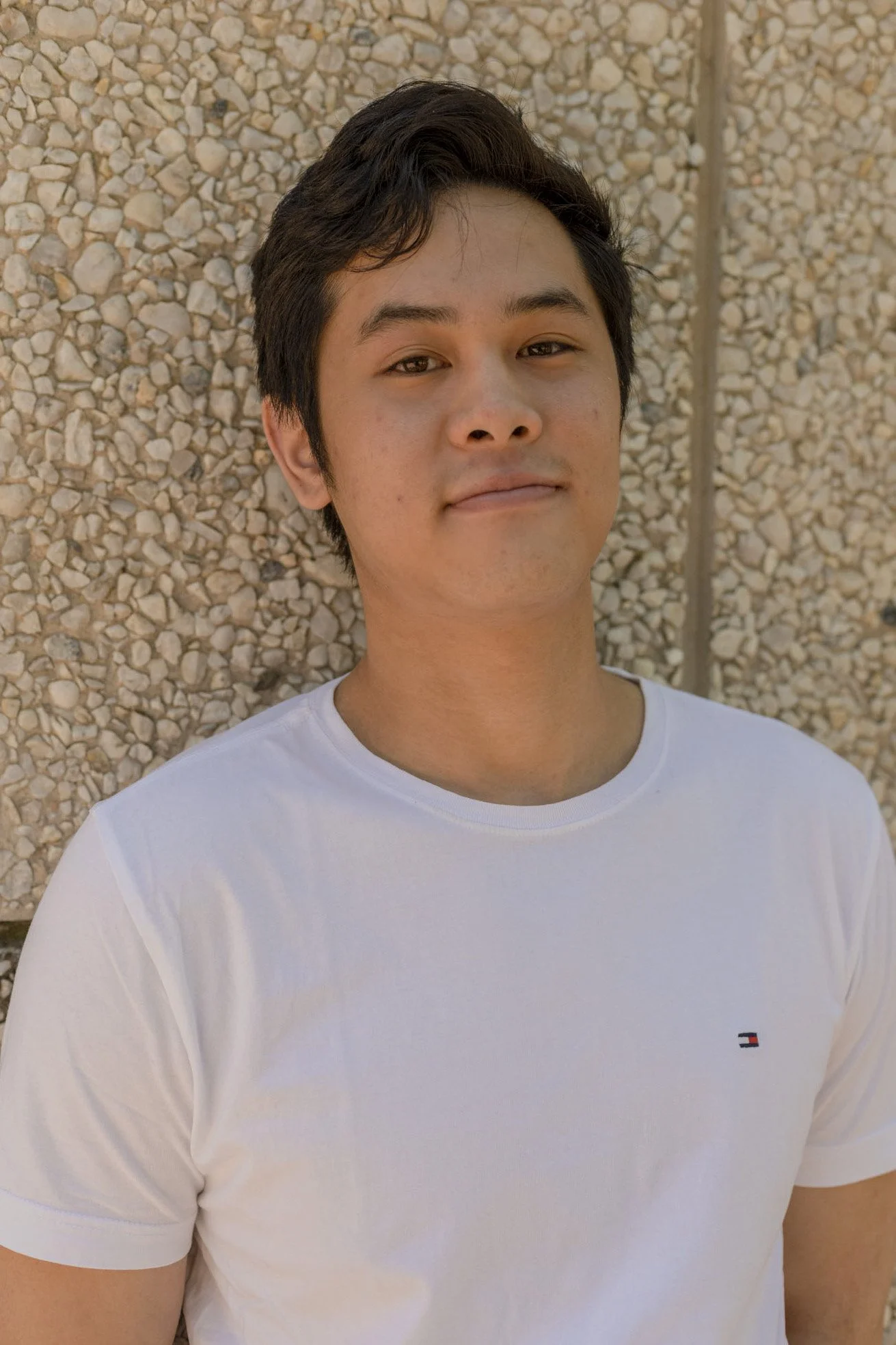

Brandon Winsley | A question for friends not strangers

As someone who grew up in the suburbs of Sydney among a mixed population of ethnicities, I have never questioned my identity as an Australian. I have always felt accepted and included.

When I was younger people asked me where I am from and I told them I am from Indonesia. It never felt like they were implying that I wasn’t Australian, it just felt like they wanted to know my ethnic background. The people who usually asked this could have been anyone from my classmates to older adults.

As I got older, my peers from non-Australian backgrounds would instead ask ‘What’s your background?’, or ‘What’s your ethnicity?’. People of colour are aware of the connotations and have reworded this question as a result. Caucasian-Australians continue to ask, ‘Where are you from?’.

The question only annoys me when it’s unprompted. Most of the time it doesn’t. But I do remember a time when it did annoy me: I was working at a cashier and a customer asked me that question. It wasn’t relevant to anything at all and although I’m sure it was meant to be perfectly innocent, it wasn’t something I felt like sharing with a stranger.

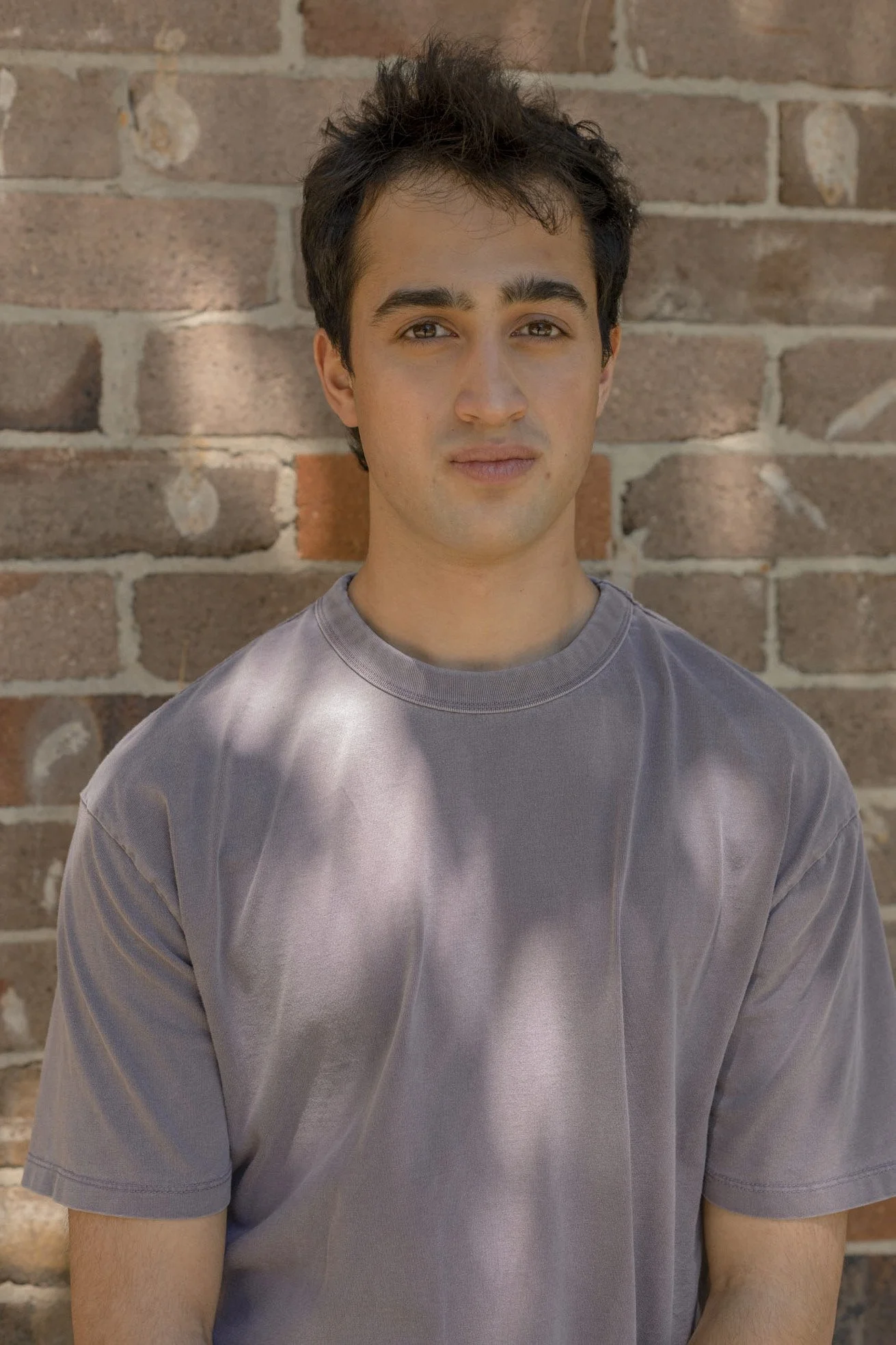

Zachary Wyatt | A question that has strengthened my identity

It's a conversation I've had countless times: ‘Where are you from?’, and then it's uglier brother trailing not too far behind - ‘No, but like really where?’.

The question rarely bothered me when I was younger, my cultural identity matched my environment back then, but as I matured it became impossible to dodge. At every new job, interaction at a party or casual coffee shop conversation I was forced to realise that I am not the preconceived notion of Australian.

Every time the questions are thrown, I walk the knife's edge when responding. I realise that how I answer will presumably dictate the way this person will behave around me. Do I laugh it off and say the North shore, hoping that it dodges the latent nature of this question and gives them the freedom to make a joke in return. Or do I give them the truth? And risk exposing myself to whatever biases this person has.

My mother is Malaysian-Indian and my father is Australian. ‘Wow, you don't look that Indian’, they’ll probably exclaim. Why does it matter if I don't look that Indian? Sometimes I wish that I had more distinct features so people could label me clearly without having to let me know their opinion of what I do and don't look like. My response is and always will be situational, I am too good at realising the angle of where the question is coming from. Sometimes it's inquisitive, but on that rare occasion, it has darker undertones. Dodging it with humour and a quick reversal usually gets me out of it. I will never understand why it matters but that is fine.

If anything it has strengthened my identity. I am who I am, and your notion of what I should look like, will never alter that.

A struggle to replace oneself culturally | Rena Hasimi

I wasn’t born in Australia, and I am not Australian. So the question ‘Where are you from?’ does not bother me. It’s the follow-on questions, comments and unconscious biases used to express perceptions about me and where I come from that do.

Through this experience I discovered that I am in the ‘other’ category. To me that feels like a fixed identity, one that often does not reflect how I grew up or who I am. So the follow up questions and comments when I say that I am from Turkey often make me feel irritated. Sometimes I feel angry. Other times I’m too shy to continue the conversation.

‘Oh, you don’t look Turkish!’

The subliminal stimuli of the life I live in Australia; with my friends, my partner’s family and in the suburb I live in— it all contributes to my unconscious effort to assimilate. To move away from being classed as an ‘other’. I found myself adjusting my clothes, my hair style, the topics I broach during small talk. What a nonsense struggle it is to replace one’s cultural self with another. It was a terrible feeling to realise my unconscious effort.

I later understood that I don’t have to justify the way that I look, talk, or think. I am proud of my identity and who I am. I have the same friends and family and live in the same suburb. I joke now and simply respond: ‘What should I look like? A doner kebab?’

Fourth | Fourth Sutjarittham

‘My name is Fourth.’

‘What?!’

‘Fourth, like first second third fourth.’

‘Oh.. that’s cool. Did you make that name yourself?’

‘No. My parents gave me the name.’

‘Oh, where are you originally from?’

I love it when people ask me where I’m from. Because then it gives me the chance to explain my background and culture:

‘I’m Thai. We actually have three names: our nickname, first name, last name – all given to us by our parents! My parents miscarried the second and the third child, and I was the fourth one.’

So ask me ‘Where are you from?’, and I will gladly answer (and maybe give a few tips about which Thai restaurants are worth trying.

Natasha Kumar | It’s the intent behind the question that matters

When people ask the question ‘Where are you from?’, I assume they want to know where I was born. I was born in Suva, Fiji and have spent most of my life in Sydney. I have also lived in New Zealand and the USA. My mother is from Viti Levu and my father is from Taveuni.

Whilst the question comes up with Uber drivers and when I meet friends of friends at weddings, it becomes most uncomfortable when it is at the beginning of a microaggression. When it is used to reduce my identity to a culture or social group, to reinforce differences without acknowledging the nuances of a person’s identity. It can carry implicit assumptions about race, ethnicity, nationality and can be quite patronising. It is the intent behind the question that matters to me. The tone of voice, facial expressions, and follow-up questions. All of this determines how I respond to the question.

My parents learned English from an early age. I’ve never heard anyone make a comment about their accent or mine. We don’t sound like foreigners, so I presume I get asked ‘where are you from’ based on the way I look and the colour of my skin. I realised at a young age that my parents were not North Stars - they have experienced more direct racism in their lives whereas I have experienced more casual racism. My research and teaching roles at UNSW have afforded me opportunities to appreciate diversity in perspectives, viewpoints and knowledge. And call out casual racism when I see it. The experiences that disappointed me most were not at the workplace; they involved people that were close to me at the time, such as the parents of a long-term boyfriend, who saw me, and any other non-white Australian through a tokenistic lens.

Sachini Wewegama | Not all alike, and that is a great thing

For so long the mostly well-intentioned and curious question, ‘Where are you from?’, has created an internal conundrum for me. I have hesitated to respond, not sure whether to answer with my parents heritage or which part of Sydney I’m from.

Moments like these have always made me feel like an outsider in the country I call home. But this shouldn’t be the case, I’m a proud Australian and there are so many of us with rich cultural backgrounds.

In my case I was an Australian citizen from birth, but born in Singapore with a Sri Lankan heritage. I lived in Six countries before moving here permanently when I was 7.

I hope to help change the narrative for acknowledging and embracing the rich diversity among us all. Australians don’t all look alike and that is a great thing.

Xiaoqi Feng | A love of sharing ‘insider knowledge’ about my hometown

It’s not often that I’m asked: ‘Where are you from?’ Maybe that’s because the pandemic has had such an impact on who we communicate with and how.

I have been asked a similar question recently though: ‘Where did you grow up?’

Once I was doing a live online workout and my trainer asked me this question. We were talking about my travels before the pandemic and the trainer shared that they have Chinese ancestry and were born in Australia. I mentioned that I grew up in Beijing and asked them if they had visited. ‘Not yet’ they said. ‘But it is certainly on the list of places to visit.’ I enjoyed sharing tips on what to see and do in Beijing. It’s such a big city and I know lots of people like to have a little ‘insider knowledge’ about my hometown.

Another time, after the Sydney lockdown had ended, my husband and I travelled to the South Coast for a holiday. Our Airbnb host - a local middle-aged Aussie - couldn’t have been nicer. The host asked me if I am from China and when I said yes, they asked which part, adding they’d been amazed and enjoyed their trip to Beijing and Shanghai a few years ago. I was very happy, as I haven’t had a lot of casual conversations about holidays in general since the pandemic began.

Telling people where I grew up makes me happy, and maybe a little bit proud too. I like to share the destinations, the food, our social rituals and the festivities that people can explore when they visit Beijing and other parts of China.

I remember learning lots about ways of living, cultures and customs in Western countries while growing up in Beijing. But I find people growing up in Western countries don’t usually learn about the diverse population, geography and gastronomic delights of China. Especially hotpot - which is such a fantastic communal and joyful dining experience!

Anyway, if you plan to visit Beijing, I would be happy to tell you all I know.

Embracing both sides of where I’m from | Evan Leung

I get asked this question a lot. For example, just a week ago when I was at dinner. But I think most, if not all, of these kinds of questions are asked just to get to know you better.

I do remember being in primary school and being asked this question a lot. I would say ‘I am from Australia’, and (you’ve probably heard this before), but they respond— ‘Naaaa… but like where are you really from?’. That made me sad because I thought I was Australian, and what they are basically saying is you're not really Australian, because you are not white.

This made me confused and out of place as a kid. But I am pretty understanding and I don’t feel like people ask things like this on purpose. I believe the people are generally trying to be nice and trying to get to know me better. There’s no ill intent for me (even if it’s an inherently bad question to ask).

At the same time, I still remember after these primary school experiences, when people would ask me ‘Where are you from?’, I would just make myself say:

‘I’m from Australia, but my background is from Hong Kong.’

I still say it like this today.

With that response, I don’t get asked questions like: ‘Where are you really from?’, and life is good embracing both sides of where I’m from.

Reem Almasri | I always stood out, because of my cultural identity

In my case, it has always been ‘So then, where are you from?’, because it usually comes as a follow-up statement after a load of assumptions that are based on my appearance: ‘Are you from Afghanistan? Iran? Turkey?’. ‘Oh, so then, where are you from?’.

I've never minded being asked that question. I don’t blame people for not knowing much about the population and diversity of my country and religion - those things play a role in how I dress and behave. I answer: ‘I am proudly from the beautiful country, Syria’.

‘Hmm, is this in Dubai?’, they’ll respond.

I don’t blame anyone for not knowing much about geography, but it annoys me when I need to educate others about how someone’s appearance and faith doesn’t necessarily mean they are from a certain land. Did you know that Syria has people who practice Christianity and Druze as well as Islam?

I stopped relating my hijab, skin tone, thick eyebrows, and bulbous nose back to the country I was born in, because I have never lived in my country. Nor have I experienced the feeling of holding a passport to a country that gives you a hand when you really need it. Growing up, I was continuously travelling and migrating from country to country in search of a better future. But I always stood out, because of my cultural identity.

So I realised that no matter how many times I try to separate the way I look from where I came from, this question will always be asked. Whether that’s in a job application, an interview, an online form, or in face-to-face everyday conversation.

The most important aspect of this question is to not judge anyone before or after knowing their ethnicity.

Rohitash Chandra | Complexity that gives meaning to identity

About a century ago, my ancestors known as the Girmityas travelled from India to Fiji. They were told that they were being recruited for employment somewhere in India. They later found their way on a months-long journey to a remote island on the other side of the world, called Fiji. Although the majority of the Girmityas settled in cane farming communities, in Western and Northern Fiji, a minority group took care of dairy farming in the Eastern side of Viti Levu - the largest island of Fiji. My ancestors settled in Vunidawa, Viti Levu. I am from Nausori: a town 20 kilometres from the capital, Suva.

My dad was a farmer. Everyday after school we would work on our farms with him. From the age of six I was assigned the task of taking care of the livestock. There were no employment options available and not much given by the government. As well as poverty and politics, we lived with adverse climate conditions. For a couple of months per year we had tropical cyclones, and the most damage occurred within poor farming communities like ours.

My dad was an expert in planting Bele: a green leafy vegetable. The cyclones would destroy them, and whatever was left would be taken by the floods. In the aftermath of Cyclone Kina, in 1993, we had almost nothing. The roof of our kitchen blew off and we survived the night under a table. During the weeks ahead, we had no electricity and minimal food supply from the government, because there was racial discrimination in the distribution of supplies. We survived by eating discarded potatoes thrown out from the shops. My mom was managing the livestock farming on just what was needed for subsistence - and so we survived.

Discrimination became a norm and hard work was the only option I had in a family living in extreme poverty. Our nation had major political unrest (a coup), in the year 1987, when I was 3 years old and then again in the year 2000 when I was 16. I can still remember the terrifying experience of large stones falling on our corrugated iron roof. There was violence. Houses and shops were looted and burnt based on racial grounds. Our close relatives had their houses destroyed and we were considered lucky for only the stones in our footsteps. I can't imagine what would have happened if the mob entered our house that year.

Our lives changed drastically due to these coups. We were targeted because of our race and cultural identity - where the economic growth and success of the Indian community was seen as a threat to the nation. This is how the country acknowledged us for our contributions. After the coups new reforms were brought in to implement race-based policies that meant Indians were seen as second class citizens. This was a way to ensure political stability. Scholarships and government jobs were given based on racial identity rather than merit. Our relatives were evicted from their farms, when the land lease was over, and they were not compensated for the development they had made. They had their houses taken and had to settle elsewhere.

I secured a full scholarship from the government in 2003 to undertake a Bachelor of Science in Engineering Technology and Computer Science at the University of the South Pacific. I later continued my studies in Wellington and then moved back to Fiji after I graduated in 2012. In 2016, I moved again when I took a Research role in Singapore. I felt that Singapore was far from Fiji and also a bit constrained to a small crowded place. I had become accustomed to the rural farming community lifestyle. I love forests and the ocean and wanted to be close to Fiji. But instead I moved to Sydney and got a job at UNSW at the beginning of 2020. Before I could get used to the campus life and regular teaching activities, pandemic restrictions took over and I had the challenge of online teaching to face.

I love art and literature and spend a lot of time watching movies, especially art-drama themes from international cinema. I watch mostly Indian movies, with different languages - Hindi is my mother tongue so Bollywood movies naturally make up the most of what I have been watching over the years. But I also watch Marathi, Bengali, Tamil, Telugu and Malayalam movies from Indian cinema. I love Hindu and Buddhist philosophy and I write poetry. I always say: my mind is a scientist and my heart is a poet. At times, it is a challenge to see things from these two perspectives.

We are fifth-generation Fiji-Indians. Our ancestors were the key contributors to economic development through cane farming that made Fiji the economic hub of the South Pacific. I would like to pay tribute to the Girmitiyas for their blood, sweat and tears. We must not forget that the economic foundation of Fiji has been built on slavery, also known as the indentured labour system.

Rameen Zahra | I was born everywhere I have lived

As a new immigrant in Australia it’s not uncommon for me to hear this question. While I understand being asked this often triggers other people, I can safely admit that it does not bother me. Not one bit! In fact, I almost welcome it.

To me, Where are you from? is a way of reaching out - why would anyone want to ask me that question unless they want to get to know me? Sure, there are more polite ways of striking up a conversation, but being who I am I like to see it as an offer for a handshake, albeit a socially awkward one.

And so I happily answer them, and proudly say: ‘I am from Pakistan’.

‘Where is that?’ they ask sometimes.

‘You know India? Well, I am their neighbor!’, I’ll respond with a smile.

To me, not everything has to be a personal attack. Sometimes Where are you from? can simply mean Where are you from? and not Why are you here?

We live in a world divided by man-made borders; nationalities, ‘exotic’ skin tones and varied accents. We are all so different, yet deep down we are so similar too. Let’s celebrate the differences instead of taking offence. I like to give every stranger who asks me where I am from the benefit of doubt. Instead of assuming superiority in their tone, I pay more attention to the natural curiosity of a fellow human who seems to really want to know. I give them an answer that may or may not satisfy them. How I respond to the question is the only thing within my control.

Perhaps my passing encounter with someone will affect their perception of the next stranger they come across. And then maybe the world will become a better place. I believe in the goodness of people. Too many of us out there, including myself, are supremely misunderstood. I like to play my little part in helping these misunderstandings by starting conversations on a positive note.

Conversations with strangers are so rare after all – I want to make the most of them.

You’d be surprised to know that despite that, sometimes I still struggle to answer the question. After all, I was born everywhere I have lived.

Beatrice Lee | Proud to come from a land with a multitude of rich cultures

From the moment I arrived in Australia my life has been a never-ending guessing game of ‘Where are you from?’. As someone who speaks with a slight tinge of a Malaysian-Singaporean accent, quite often the question ‘Where are you from?’ turns into a simple conversation starter.

This question is quite ambiguous. Which country was I born in? Where was I raised? Where do my ancestors come from? Where do I call home? What languages do I speak? This question can have different meanings.

Growing up Malaysian-Chinese, I get a lot of questions about how my ethnicity is ‘Chinese and not Malay’, even though I’m from Malaysia. Having to explain this to a stranger in Australia is way more complicated than you think.

Don’t get me wrong. I love sharing my cultural background. I am proud to be Malaysian. I am proud to come from a land with a multitude of rich cultures; Malaysians can mix four languages in one sentence. I am proud of the delicious Malaysian cuisine, from Nasi Lemak to Hainan chicken rice – you name it, we have it. Not to mention, I am proud to come from the land that produces the king of all fruits—Durian!

After living in Sydney for years, and not being able to go back to Malaysia due to the pandemic, I found myself starting to doubt the answer to the question of where I consider to be my home.Deep down, I don't know the answer.

Having said that, I don’t mind having the conversation - and I don’t mind answering the question – but sometimes, it’s exhausting to keep explaining my nationality and ethnic background…

I think the take-home message is that next time, when you are about to ask someone ‘Where are you from?’, take a moment to reflect before asking. Try changing the question up a bit or ask in a more polite way instead of the super straightforward: ‘Where are you really from?’.

Stephen Liang | Not an ABC, but no stranger to Australia

You would assume people like us get asked this kind of question often - you are probably right. With a distinctly Asian appearance, Where are you from? is almost always the first question I’m asked when I meet new people.

People often ask very directly. I can usually sense beforehand if they want to know which country I am originally from, or if they just want to know whether I live in Kensington or not.

I used to struggle to answer the question. I'm not an ABC (Australian-Born Chinese), but as a person who has spent 8 years overseas I'm no stranger to Australia either.

As time goes by, I feel that I have to welcome this question as there is no way to escape from it. Nowadays, I don’t mind being asked the question. Sometimes I even start with the story of where I’m from before they ask:

‘Hi, I'm Stephen. I'm originally from China. I'm also from Sydney. I spent 8 years overseas. I love Australia and I am proud of being Chinese. Now, could you tell me where you are from?’

Ayush Bhardwaj | Where are you really from?

This morning, a colleague of mine at work asked me Where are you from? Usually I curate my answer to this question, depending on who I’m speaking to, and how much I would like them to know about me.

‘I’m from India and my background is from Qatar’, I responded.

The person asking was a colleague, who I had met for the first time on the job. He started looking at me in a particular way when I said India - like an image of me was set in his mind, and there was nothing I could do or say to change it.

I would have preferred to respond in a way that actually explained who I am, my culture and where I come from.

Saira Arias | These things sort of do a number on you

I'm not fussed about anyone's interest in my culture or background. In fact, I don't think most people are. Despite that, it would be obtuse to overlook the implications that those specific words carry.

‘Where are you from?’

As if home for me isn't a 45-minute train ride from Central Station - give or take how reliable Sydney transport is that day.

Most, if not all of my encounters with this specific question take place around the city and in the Eastern parts of Sydney. Sometimes I think it's this kind of accent I have going on: I'm super heavy with my pronunciation of the letter R.

I didn't really hang out with other kids all that much, before I started at primary school. I only ever spoke to my parents and their Filipino-English was molded on American-English. So I always felt like people who asked where I'm from were assuming that I was an international student.

I am visibly brown but yes, my accent says otherwise.

If anything it's still a loaded question, especially for someone who's still trying to reconcile with never being ‘entirely Filipino’ or ‘entirely Australian’, at least culturally.

To some it may be obvious that there's nothing actually wrong with this. Cultural differences should be celebrated after all. Though, when you've grown up asking your dad to stop sending you to primary school with rice in your lunchbox, these things sort of do a number on you.

‘I'm from South-West Sydney.’

People who ask me ‘Where are you from?, usually ignore this. Instead, they'll specify and persist until they get my ethnic background. I'll go through the motions. In the end, it really shouldn't have to be on me to turn this into some kind of teaching moment.

Kiara Asuzu | A whole is greater than the sum of its parts

‘So, where are you from?’

The first few times I was asked this question I was a child, and always responded with Sydney, Australia.

My answer was always met with awkward umming and ahhing, or a follow-up question asking me to be more ‘specific’.

By the time I was a little older, I learned to read between the lines, and tailored my response accordingly:

My mum is Japanese and my dad is Nigerian.’

To this day, I am continuously asked this question. Funny how it’s 2021 and many people still don’t (or refuse to) understand the basic difference between nationality and ethnicity.

Despite the improperly phrased nature of this question, it’s the ethnically ambiguous individuals on the receiving end who are forced to grapple with the unpleasant connotation it holds—you don’t look like you belong here.

Upon answering ‘correctly’, everything clicks for my interrogator(s) and my existence is justified:

‘So that’s why you’re good at x, y, z!’...’That’s where you get your hair from!’…*Insert more rationalisations attributing my traits to my Japanese and/or Nigerian heritage*

This part of the interrogation is particularly jarring.

My identity is not something that can be defined by a Venn diagram. As stated by Aristotle: ‘A whole is greater than the sum of its parts’. While my ethnicity has shaped much of my identity, my existence amounts to more than the fact my Japanese mother and Nigerian father brought me into the world.

Ironically this attribution exercise, designed to discern my being, results in further confusion. Though many attempt to bind my attributes to my ethnicity, I have never felt wholly recognised or accepted as a member of either group.

However, what I’m not confused about is where I’m ‘actually’ from.

I’m from Sydney, Australia.

Nayonika Bhattacharya | Stories full of strength, resilience and humility

There is a rich history I hold in my smile, in the depth and detail of my features. The rolling of my r's, and the connection to home in my accent, are just a speck of who I am and who came before me.

As an international, queer, woman of colour; thriving with a disability and as a migrant is often an accomplishment I take for granted, but this opportunity serves as a reminder that migrants, especially women of colour, are here to challenge stereotypes and break barriers.

Sharing my story in a small way immortalises that a lot of the faceless, nameless women who feel like there is no opportunity out there, are here to stay. We can create our own space and grow to new heights, despite facing a number of obstacles.

It is important to me to remind people that our migrant stories are full of strength, resilience and humility.

Where are you from? UNSW, based on the original ongoing project Where are you from?®, founded and curated by Sabina McKenna.

All artworks © the artist. Online exhibition, photos and videos © The University of New South Wales. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form without the prior written permission of the copyright holder, unless the use falls within an exception of the Copyright Act (such as research or study).