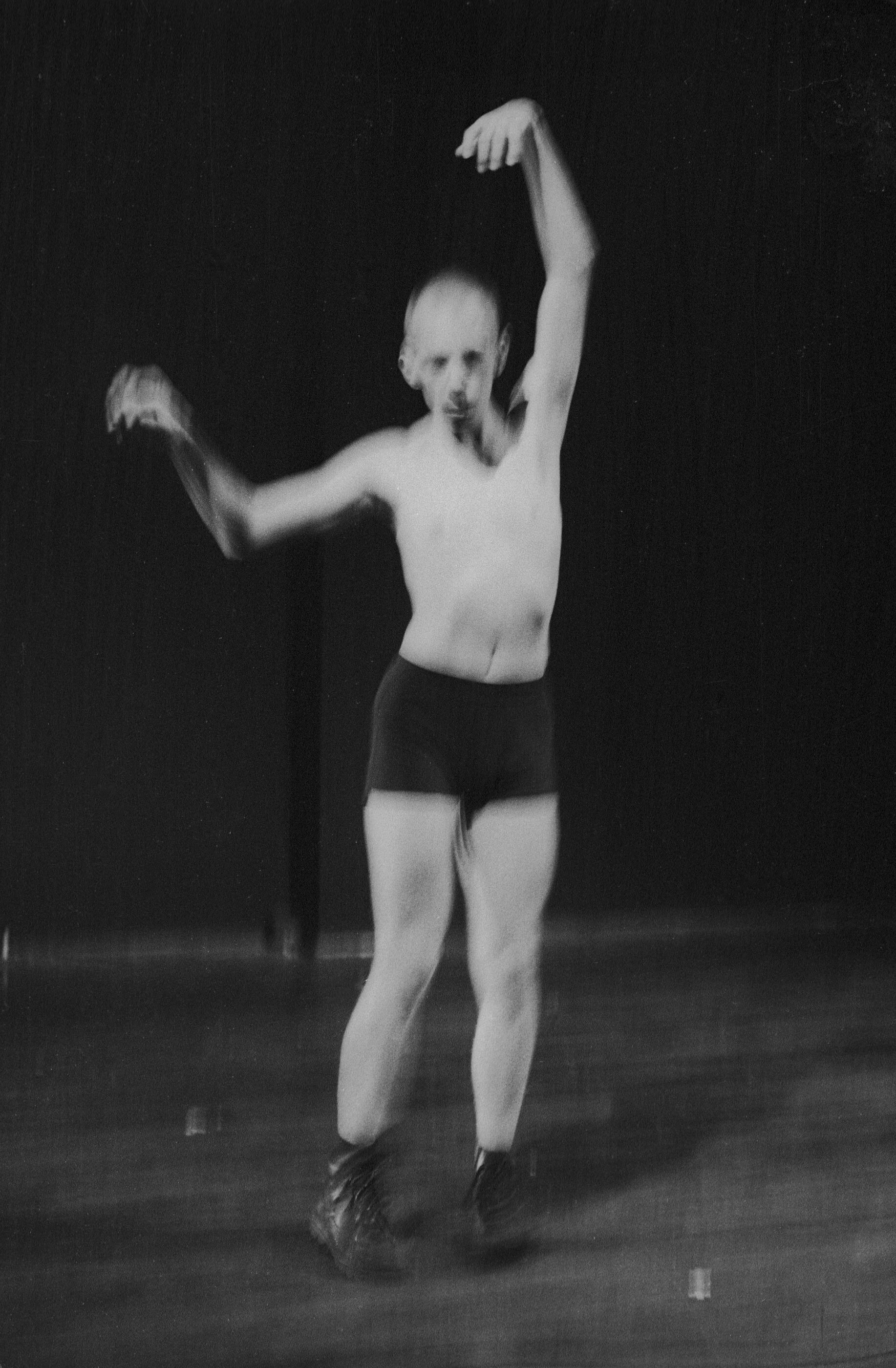

Piece (1996)

The first solo I ever presented in Sydney was a Butoh-inspired piece set to Giacomo Puccini’s aria O Mio Babbino Caro sung by Victoria de Los Angeles. It was just under 3 minutes and I performed it on the final night of Performance Space’s Open ’96. The performance garnered me my first mention in RealTime. Caitlin Newton-Broad wrote: “Martin del Amo gave a treasure to his audience, set simply to the ubiquitous opera number Oh my beloved father.” Only one sentence, but not a bad start!

Piece, Open ’96, Performance Space, Sydney, 1996

Performer: Martin del Amo

Photo: Heidrun Löhr

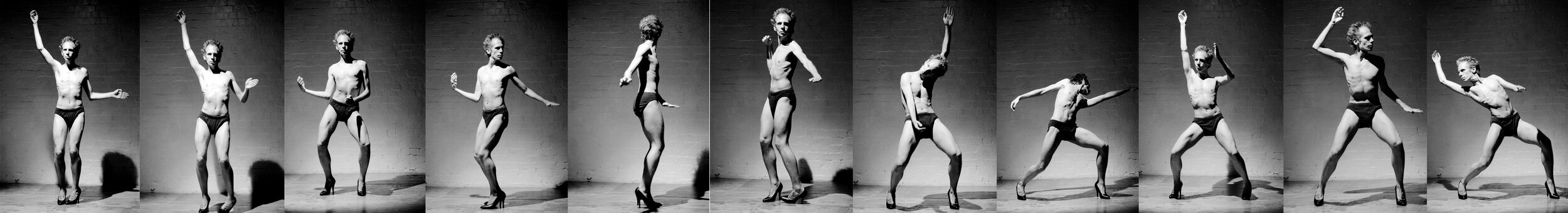

A Severe Insult to the Body (1997)

I created A Severe Insult to the Body over a 3-month period in 1997. Its staging – I performed the piece in underpants and high heels, lit by a single spotlight from above – was a nod to the Queer Cabaret aesthetic prevalent in contemporary performance circles at the time. Choreographically, it was the first time I explored a strategy I would later call ‘physical fragmentation’ – the body is divided into separate body zones, each of which is choreographed individually, independently from each other.

A Severe Insult to the Body was reviewed in RealTime at two different performances, with vastly different responses. Richard James Allen wrote in his review of Performance Space’s Open Season 97: “My Beautiful Laundrette meets Butoh Workshop 101 on the set of Silence of the Lambs. … What excuse is there for this kind of contortion?” Covering Sidetrack’s Contemporary Performance Week 8 a few months later, Virginia Baxter and Keith Gallasch wrote: “… Martin del Amo was all spidery unease in the hypnotic A Severe Insult to the Body.”

In subsequent years A Severe Insult to the Body became somewhat of a signature piece of mine. I performed it in many different versions, in a variety of contexts, over a long period of time. Its last – maybe final – performance took place in 2017, as part of a residency showing at Critical Path for Dancing Sydney : mapping movements : performing histories. It marked the 20th anniversary of its creation.

A Severe Insult to the Body, Omeo Dance Studio, Sydney, 2003

Performer: Martin del Amo

Photo: Heidrun Löhr

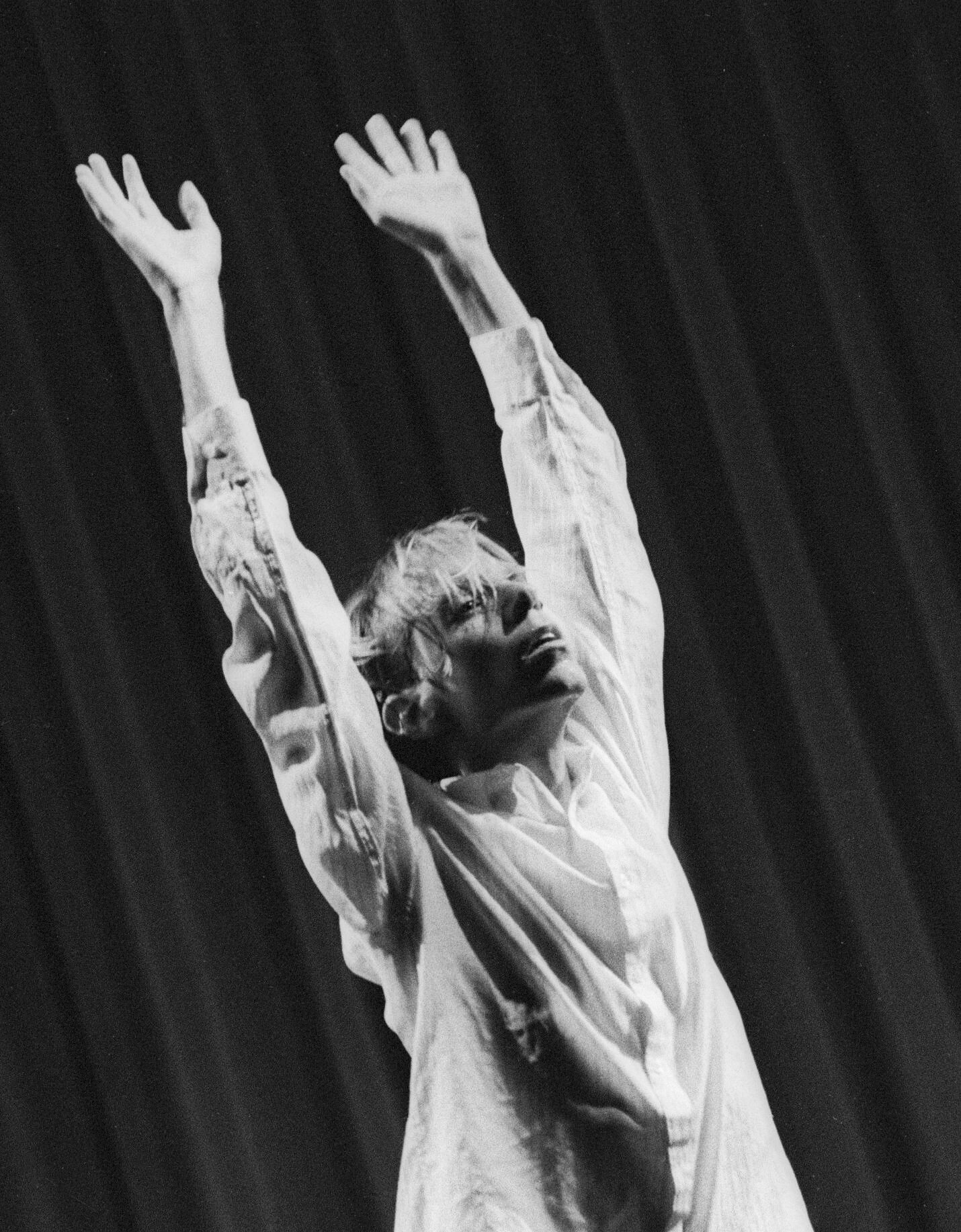

Unsealed (2004)

Unsealed is a 40-minute piece fusing idiosyncratic movement and intimate storytelling. Exploring the concept of ‘losing it,’ its aim was to playfully jump-cut between literal and metaphoric states of desire and deterioration. It was presented as part of a dance program at Performance Space called Parallax. Even though my work had been mentioned in RealTime before, it was the first time that I received a full-length review. What set it apart from the extremely positive reviews published in daily newspapers such as The Sydney Morning Herald and The Australian, was that it moved beyond mere evaluation and actually discussed my piece as a work of art, analysing and interpreting it.

After months in the studio by myself, spending countless hours imagining what the work’s impact might be on an audience, I strongly appreciated a critical approach that seemed to enter into a direct dialogue with my practice. In his concluding paragraph, Keith Gallasch wrote: “At 40 minutes, Unsealed is a complete, quietly disturbing, confiding and important work from Martin del Amo that makes an art of walking, invites our empathy and offers a sad paean to the virtues of melancholy.” Even though these sentences clearly demonstrate Gallasch’s appreciation of the work, what makes them stand out for me most are their interpretive insight.

Unsealed, Parallax, Performance Space, Sydney, 2004

Performer: Martin del Amo

Photo: Heidrun Löhr

Under Attack (2005)

In 2003, my partner of many years – Benjamin Grieve – tragically died. This event plunged me into a prolonged state of grieving. In the following years, I worked feverishly, creating at least one work a year, alongside numerous studio showings and countless appearances in short works programs. Even though many of these works explored themes such as trauma, loneliness and instability, I was adamant that none of them were actually about my grief per se. I was aware, of course, that a lot of people interpreted it that way.

Needless to say, I found fault with the opening sentence of Keith Gallasch’s review of my 40-minute work Under Attack, presented at Performance Space’s Solo Series #1, produced by Onextra. The piece addressed the fragility of the human body under constant threat of aggressive forces – from digitilisation to decomposition. Gallasch wrote: “Following his Unsealed of 2004, Martin del Amo’s Under Attack is another utterly engrossing solo, the second part in a trilogy, this one moving in even closer on the first part’s grief (the artist’s for the death of a lover) …”

It took me a long time to understand that maybe artists are not always the most reliable to comment on what motivates them to create work, as they aren’t always fully aware of what drives them. Now, years later, I still maintain that I never deliberately set out to make work that would help me process my grief, but I can accept Gallasch’s interpretation as a valid one.

Under Attack, Omeo Dance Studio, Sydney, 2005.

Performer: Martin del Amo

Photo: Heidrun Löhr

Can’t Hardly Breathe (2006)

Can’t Hardly Breathe was conceived as a darkly humorous exploration of the relationship between obsession and trauma. It ran at about 25 minutes and was presented at Performance Space as part of a double-bill Mixed Double, with spoken word performer and writer Rosie Dennis, with whom I shared a regular improvisational practice at the time.

When working on my solo Under Attack the year before, I decided to call it the second part of a trilogy with Unsealed being the first. Once Under Attack was completed, however, I realised that it made for a perfect companion piece to Unsealed and that a third piece was not needed. By the time I presented Can’t Hardly Breathe, I had begun preparations for a new full-length work set to premiere the year after and which would take me into new thematic territory. As a result, Can’t Hardly Breathe became a transitional piece – thematically related to its predecessors but already employing devices that I intended to explore further in the new work.

Unfortunately (and characteristically attentively), Keith Gallasch had not forgotten my talk about a trilogy and introduced the piece in his RealTime review as “the third part of Martin del Amo’s trilogy (the other 2 are Unsealed [2004] and Under Attack [2005]) …” About the work, he said: “While not as structurally satisfying as its predecessors, Can’t Hardly Breathe is nonetheless memorable.” I admit that it’s a bittersweet experience when a review of your work is partially critical and you have to concede that the criticism is warranted. Luckily, the review ended on an encouraging note: “The desire to see all 3 works on the same program is unlikely to be met given the demands on the performer of just one of them—a pity, so let’s hope they’ve been seriously documented.”

Can’t Hardly Breathe, Mixed Double, Performance Space, Sydney, 2006

Performer: Martin del Amo

Photo: Heidrun Löhr

Never Been This Far Away From Home (2007)

Never Been This Far Away From Home marked a thematic shift in my work as solo artist. Previous pieces had explored themes of physical and mental instability, presenting the self as a direct target of uncontrollable forces. This work introduced a more active, adventurous persona, keen to navigate both the exhilaration and dangers that come with moving away from ‘home’ beyond one’s comfort zone, into uncharted territories.

Produced by Performance Space and presented at its new home at Carriageworks, the piece was my first full-length solo work, shown outside the context of a double- or triple-bill. Not sharing a program with other artists guaranteed more creative freedom but also added pressure. Audiences would come to see my work and my work only. The success of the piece – or its failure – depended entirely on me and my creative team. What increased the pressure even more was that Never Been This Far Away From Home was the first piece to be presented at Carriageworks’ Bay 20. These circumstances mirrored the themes the work purported to explore in a scary way. This was definitely a journey into the unknown …

RealTime reviewer Jan Cornall seemed to be reading my mind: “The work of the solo performer is always risky. What if the telling fails, what if the audience doesn’t get it, what if they fall asleep—what if they want me to shut up and just dance?” To my great relief, Cornall concluded that I mastered the challenge. “Del Amo doesn’t falter over such concerns, but methodically carries out his set task—to share with us the journey of his explorations: notions of home, the void of fear, danger and the unknown, where the edges of dreaming and reality meet.”

Never Been This Far Away From Home, Clare Grant’s home and Carriageworks, Sydney, 2007

Performer: Martin del Amo

Photo: Heidrun Löhr

Never Been This Far Away From Home (2007)

Never Been This Far Away From Home marked a thematic shift in my work as solo artist. Previous pieces had explored themes of physical and mental instability, presenting the self as a direct target of uncontrollable forces. This work introduced a more active, adventurous persona, keen to navigate both the exhilaration and dangers that come with moving away from ‘home’ beyond one’s comfort zone, into uncharted territories.

Produced by Performance Space and presented at its new home at Carriageworks, the piece was my first full-length solo work, shown outside the context of a double- or triple-bill. Not sharing a program with other artists guaranteed more creative freedom but also added pressure. Audiences would come to see my work and my work only. The success of the piece – or its failure – depended entirely on me and my creative team. What increased the pressure even more was that Never Been This Far Away From Home was the first piece to be presented at Carriageworks’ Bay 20. These circumstances mirrored the themes the work purported to explore in a scary way. This was definitely a journey into the unknown …

RealTime reviewer Jan Cornall seemed to be reading my mind: “The work of the solo performer is always risky. What if the telling fails, what if the audience doesn’t get it, what if they fall asleep—what if they want me to shut up and just dance?” To my great relief, Cornall concluded that I mastered the challenge. “Del Amo doesn’t falter over such concerns, but methodically carries out his set task—to share with us the journey of his explorations: notions of home, the void of fear, danger and the unknown, where the edges of dreaming and reality meet.”

Never Been This Far Away From Home, Clare Grant’s home and Carriageworks, Sydney, 2007

Performer: Martin del Amo

Photo: Heidrun Löhr

It’s a Jungle Out There (2009)

By 2009, I had consistently presented solo works for over five years, becoming somewhat of a fixture in the Sydney dance and performance scene. It slowly dawned on me that it wasn’t as easy to surprise audiences as it used to be, let alone ‘make a splash.’ People seemed to have formed a clear idea about who I was as an artist and what kind of work I would make. I realised that in order to grow as an artist and not constantly repeat myself, I would need to keep questioning my approach to creating and presenting work. While developing It’s a Jungle Out There, a new full-length work investigating the modern-day city as an ever-changing organism, I decided to conduct a series of research excursions. They were designed to heighten my perception of the city’s impact on the body, and included walking backwards through Sydney’s CBD, moving blindfolded alongside Parramatta Road during rush hour and crawling on all fours in The Rocks.

This set of circumstances was not lost on Pauline Manley, who wrote in her review for RealTime: “Martin del Amo is ubiquitous. He pops up wild haired and undie-clad so often on the Sydney underground landscape that expectation is fashioned by familiarity. Yet he surprises. His insouciant belief in the inherent worth of what he has to say gives his work a trademark intensity that results from the piquancy of fascination and research. Whatever del Amo is investigating, it is done with a ferocious and meticulous attention that is a lust to discover, uncover and reveal.”

It is probably also worth mentioning that in the late 2000s, Sydney’s independent dance and performance landscape started to rapidly change. Suddenly presentation opportunities were more likely to spring up in Western Sydney than in Sydney’s metropolitan area. Tellingly, It’s a Jungle Out There was the first work I did not premiere at Performance Space in over a decade. Instead, its final development and presentation were commissioned by Campbelltown Arts Centre. The piece, however, was presented by Performance Space at Carriageworks a year later as part of a tour that also included seasons at Dancehouse Melbourne, and Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts (PICA).

It’s a Jungle Out There, CBD Sydney, 2009

Performer: Martin del Amo

Photo: Heidrun Löhr

What Good Is Sitting Alone In Your Room? (2010)

Around 2010, the focus of my choreographic practice started to shift as I gradually made the transition from solo artist to choreographer of works for others. Even though I did not create any new long-form solos for myself after 2009, I never gave up performing. Occasionally, I even presented a new short piece. What Good Is Sitting Alone In Your Room is a case in point. Originally created for Dance History at Campbelltown Arts Centre in 2010, the piece is both a tribute to and a deconstruction of the famous Bob Fosse style. It is set to a track from Gail Priest’s album Presentiments of the Spider Garden and contains the only high kick I have ever performed. Publicly that is …

Keith Gallasch and Virginia Baxter reviewed the work for RealTime when I performed it as part of the IOU Dance Solo Series in Spring Dance 2012 at Sydney Opera House. They wrote: “Del Amo’s trademark ambulatory movement is replaced by a series of poses that evoke the choreography of Bob Fosse but without the steps from which they would usually resolve—it’s funny, quite sexy, eliciting amused recognition from the audience.” I remember being surprisingly pleased with the review, especially because it described the piece as “sexy”—not an adjective I had ever come across in previous reviews of my work. It temporarily alleviated my anxieties around being an ageing dancer.

What Good Is Sitting Alone In Your Room, IOU Dance, Io Myers Studio, Sydney, 2011

Performer: Martin del Amo

Photo: Heidrun Löhr

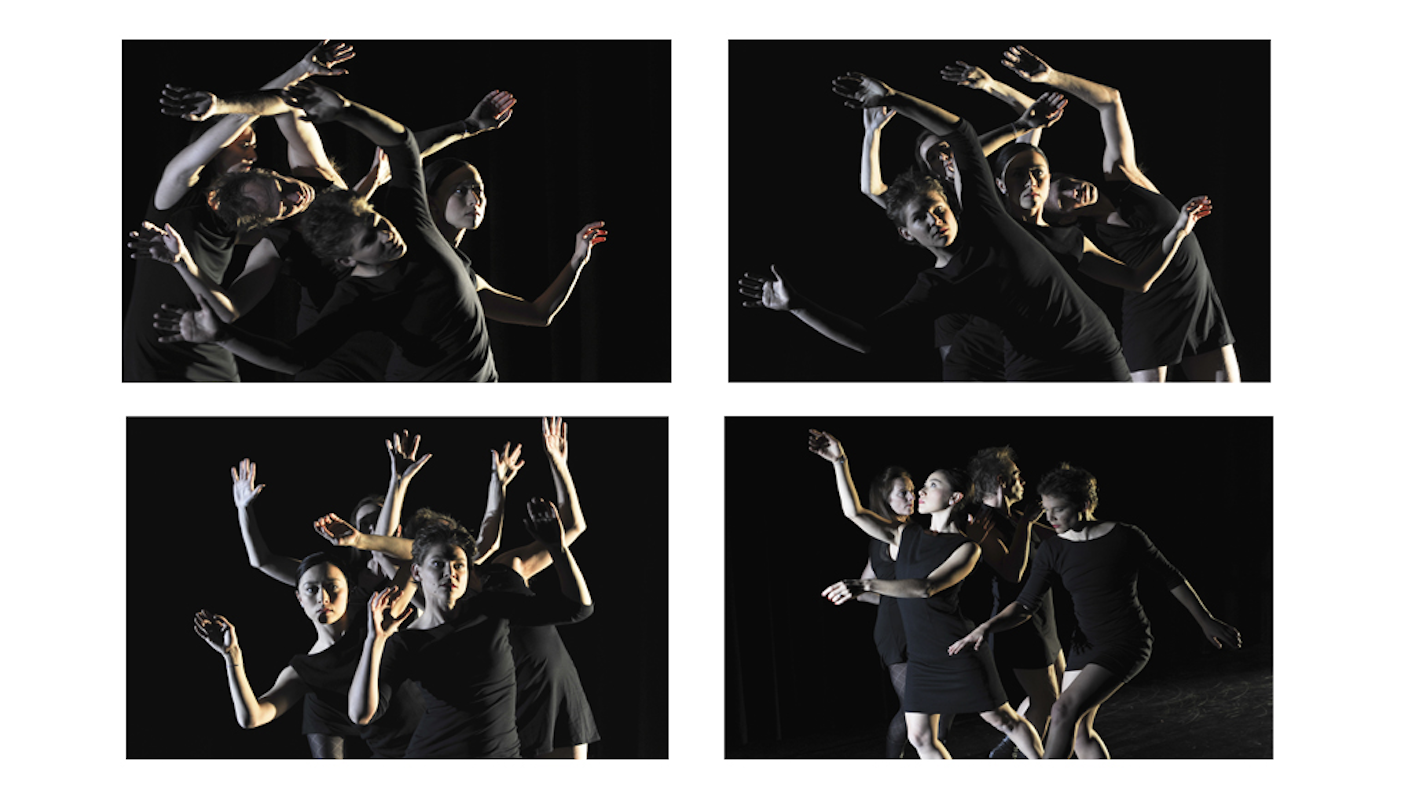

Mountains Never Meet (2011)

The idea for Mountains Never Meet dates back to 2008 when I was commissioned to create a work for LINK, West Australia Academy of Performing Arts’ graduate dance company. The point of departure for the piece was to investigate the difference between walking and dancing and if, in fact, it was as significant as often perceived. The resulting work featured simple physical actions such as walking, running, skipping, standing, lying and jumping on the spot. Simultaneously it retained a maximum level of complexity in terms of choreographic devices related to speed, direction, levels and patterning. A few years later, when collaborating with footballer-turned-performance maker Ahilan Ratnamohan, I decided to remake the work but this time with a cast of untrained young men from Western Sydney. The idea was to see if, by relocating the original material within a diverse and dynamic community such as Western Sydney, the work would gain new layers of meaning. I was also interested in playfully challenging the notion of what dance can be and who can be a dancer.

Even though I had previously created group works for tertiary institutions and youth companies, Mountains Never Meet marked my official debut as a non-performing choreographer. It was also the first time in seven years that a work of mine did not receive a review in RealTime. In the lead up to its premiere, RealTime did, however, publish an interview with me. It was aptly conducted by Gail Priest who, up until then, had been my key collaborator, composing the soundtracks for all of my works as well as performing them live. Not surprisingly, the interview turned out to be rather candid: “Discussing his reasons for the transition from solo performer to director-choreographer, del Amo cites Kate Champion from Force Majeure who was also, at one stage, best known for her solo works. ‘Kate said you can only mine yourself for material for so long and at some point you get more interested in other people’s backgrounds, stories and ideas. I think this is exactly what happened to me. I’ve always really enjoyed working by myself and having that freedom but sometimes I thought it would be nice to work with other bodies and have another input on that level’.”

Mountains Never Meet, Riverside Parramatta, Sydney, 2011

Performers: Ravin Lotomau, Frank Mainoo, Benny Ngo, Kevin Ngo, Ahilan Ratnamohan, Mahesh Sharma, Nikki-Tala Tuiala Talaoloa, Carlo Velayo, Dani Zaradosh

Photo: Heidrun Löhr

Mountains Never Meet (2011)

The idea for Mountains Never Meet dates back to 2008 when I was commissioned to create a work for LINK, West Australia Academy of Performing Arts’ graduate dance company. The point of departure for the piece was to investigate the difference between walking and dancing and if, in fact, it was as significant as often perceived. The resulting work featured simple physical actions such as walking, running, skipping, standing, lying and jumping on the spot. Simultaneously it retained a maximum level of complexity in terms of choreographic devices related to speed, direction, levels and patterning. A few years later, when collaborating with footballer-turned-performance maker Ahilan Ratnamohan, I decided to remake the work but this time with a cast of untrained young men from Western Sydney. The idea was to see if, by relocating the original material within a diverse and dynamic community such as Western Sydney, the work would gain new layers of meaning. I was also interested in playfully challenging the notion of what dance can be and who can be a dancer.

Even though I had previously created group works for tertiary institutions and youth companies, Mountains Never Meet marked my official debut as a non-performing choreographer. It was also the first time in seven years that a work of mine did not receive a review in RealTime. In the lead up to its premiere, RealTime did, however, publish an interview with me. It was aptly conducted by Gail Priest who, up until then, had been my key collaborator, composing the soundtracks for all of my works as well as performing them live. Not surprisingly, the interview turned out to be rather candid: “Discussing his reasons for the transition from solo performer to director-choreographer, del Amo cites Kate Champion from Force Majeure who was also, at one stage, best known for her solo works. ‘Kate said you can only mine yourself for material for so long and at some point you get more interested in other people’s backgrounds, stories and ideas. I think this is exactly what happened to me. I’ve always really enjoyed working by myself and having that freedom but sometimes I thought it would be nice to work with other bodies and have another input on that level’.”

Mountains Never Meet, Riverside Parramatta, Sydney, 2011

Performers: Ravin Lotomau, Frank Mainoo, Benny Ngo, Kevin Ngo, Ahilan Ratnamohan, Mahesh Sharma, Nikki-Tala Tuiala Talaoloa, Carlo Velayo, Dani Zaradosh

Photo: Heidrun Löhr

The Little Black Dress Suite (2013)

Sometime during 2012, it occurred to me that the Little Black Dress had become a recurring costume in my work. Within a period of two years, I had used fashion’s iconic garment for three separate pieces – always a different version of it, and always to a different effect. In one piece the LBD stood for show biz glamour. In another, it lent its performer a diva-like allure. In the third piece the dress was decidedly at odds with the performer’s actions. Before long I hatched the idea to draw these pieces together in a ‘suite,’ add another two, and present them all as part of the same program.

One of the things I most enjoy about being a choreographer is that I have the opportunity to regularly collaborate with other dancers. The Little Black Dress Suite was especially exciting in that respect. It allowed me to work with three dancers whom I greatly admire and whose performance skills I’m in awe of – Kristina Chan, Sue Healey and Miranda Wheen. Best of all, in one of the pieces, we got to perform together.

Not surprisingly, given the subject matter, Virginia Baxter’s review in RealTime was peppered with fashion references and sartorial puns: “T-dress, V-dress, vintage bandeau, slimline, full-skirted, reverse wrap, Audrey style, whatever, I know that the trick with the LBD is simply to wear it well. Here Martin del Amo is the tailor and each of the dancers adds her/his own personality to the outfit to bring off the elegant display.” Baxter seemed to have as much fun with the work as we did performing it. “Finally all four dancers join in a careful pattern of slow, weaving movements in and around each other in a narrow horizontal plane to the aptly haunting song “Like An Angel Passing Through My Room.” In the end, like the iconic dress, it’s all about line and grace and these dancers, each in their own idiosyncratic way, appear to have that sewn up, carrying off the choreographer’s premise with aplomb.”

The Little Black Dress Suite, Riverside Parramatta, Sydney, 2013

Performers: Martin del Amo, Kristina Chan, Sue Healey, Miranda Wheen

Photo: Heidrun Löhr

Slow Dances For Fast Times (2013)

Even after making the transition from solo artist to choreographer of works for others, the solo remained my preferred form for a long time. Nowhere was this more evident than in Slow Dances For Fast Times, presented by Carriageworks and produced by Performing Lines. Conceived as the dance equivalent of a concept album, the work comprised 12 short solos performed by 12 different dancers. The cast included some of the most highly regarded contemporary dancers from across Australia. It showcased the diversity of the sector – cultural, geographic, artistic and in terms of age and body type. For each piece, I closely collaborated with the solo performer in the creation of a unique choreographic portrait. The work was set to a series of recorded tracks, ranging from pop favourites and dance anthems of the last 50 years to a Spanish torch song and operatic arias. It culminated in a ‘bonus track’ finale involving all twelve dancers.

In some ways, Slow Dances For Fast Times was an extension of a strand of work that I developed as a solo artist. In addition to creating full-length works, I would also regularly perform short solos set to pop songs. This allowed me to show work outside of the conventional dance presentation circuit – in clubs, at parties, short works nights and festivals. Many of them originated as birthday presents for my friends, presented one-on-one in the studio first. On the other hand, Slow Dances For Fast Times also marked my most ambitious work to date in terms of scale, logistics and production values.

In her review for RealTime, Pauline Manley wrote, “certain recurrent physicalities reveal del Amo’s choreographic proclivities: the gentle distortions of discomfort as bodies are drawn away from graceful wholeness … then there are those floating arms that trace, dangle and sway as body parts with mind. These arms are what most conjured the choreographer-body, making me miss Martin.” At the time, I felt that Manley’s compliment for me as a performer overshadowed not only my achievement as choreographer but also that of the other dancers. I was intent on establishing myself as choreographer and only too happy for people to forget my past as a solo artist. A few years on, with the benefit of hindsight, I have to say that I appreciate the notion that my work as a choreographer did not cancel out my work as a solo artist.

Slow Dances For Fast Times, Carriageworks, Sydney, 2013

Performers: Sara Black, Jade Dewi Tyas Tunggal, Benjamin Hancock, Raghav Handa, Julie-Anne Long, Jane McKernan, Sean Marcs, Kirk Page, Elizabeth Ryan, Luke Smiles, Vicki Van Hout, James Welsby

Photo: Heidrun Löhr

Songs Not To Dance To (2015)

My collaboration with Phil Blackman, a Lismore-based dance artist, started as an artistic ‘blind date’ as part of an exchange project, initiated by Campbelltown Arts Centre in partnership with NORPA (Northern Rivers Performing Arts). The aim of this initiative was to stimulate collaboration between metropolitan and regional dance makers. Over time, and after several development stages, Phil’s and my professional relationship grew into a committed artistic partnership, culminating in the presentation of full-length dance work Songs Not To Dance To at Parramatta Riverside. The piece was supported through FORM Dance Projects and produced by Performing Lines.

In Songs Not To Dance To, Phil and I set ourselves the challenge of performing to a series of ‘undanceable’ pieces of music. In attempting to do something seemingly impossible, we endeavoured to acquit ourselves, against all odds, with as much dignity, resilience and humour as possible. The soundtrack of the work included Whitney Houston’s And I Will Always Love You, Enrique Iglesias’ Hero and Jimmy Barnes’ Working Class Man. Those pop songs were interspersed with tracks from the album Book of Ways by legendary jazz pianist Keith Jarrett.

The final version of Songs Not To Dance To was not reviewed in RealTime. An earlier development, presented as part of Campbelltown Arts Centre’s Oh, I Wanna Dance With Somebody! was, however. Virginia Baxter wrote: “The two well-matched dancers are restrained as the airwaves fill with that orgy of self-affirmation, Christine Aguilera’s ‘Beautiful.’ This time, movement comes from the diaphragm. Unlike the calculated stiffness of the first piece, here the dance is angular, ungainly and then fluid; the performers working in close proximity developing a distinct weave of bodies, nearly entwining, almost but never quite intimate. Words won’t bring them down.” And later, summing up the work: “In this collaboration between region and city we experience another fulfilling engagement between two different but simpatico dancing bodies.”

Songs Not To Dance To, Campbelltown Arts Centre, Sydney, 2012

Performers: Martin del Amo, Phil Blackman

Photo: Heidrun Löhr

Champions (2017)

When FORM Dance Projects first approached me with the idea to create a football-themed dance piece, I could hardly believe my luck. I had always been fascinated with the inherently choreographic nature of group sports, particularly soccer. The prospect of making a work that would draw parallels between football and contemporary dance excited me. Early on in my conversations with FORM, we decided that the cast should be all-female as that would allow us to question pervasive notions of who qualifies as dance / sports champions in a culture that generally underappreciates the achievements of female performers, both in sport and in the arts.

Over a period of two years, the dancers and I worked closely with a team of artistic collaborators to create Champions as a large-scale work, playfully challenging what dance is and how it can be presented. Our research included consultations with the coaches, athletes and physio-therapists from the Western Sydney Wanderers FC, as well as conversations with players from the Matildas squad. Choreographic inspiration was drawn from training drills, warm up rituals, victory dances, and body language expressing triumph and defeat. Channel Seven sports presenter Mel McLaughlin came on board to provide tongue-in-cheek commentary and interviews with the dancers. The work premiered at Carriageworks’ Bay 17 in the 2017 Sydney Festival.

The greatest dramaturgical challenge in developing Champions was the question of how to harness the energy and enthusiasm of the stadium experience but not merely emulate it. According to Keith Gallasch’s review in RealTime, we almost got there: “Director Del Amo cleverly suffuses sports team movement with the characterful detail dancers can bring to walking, running, jumping, ducking and weaving and standing still in formation. There's a fine interplay between team and individuals with room for some more expressive play from the latter. Champions is never less than enjoyable, the team an impressive one, and if the overall game plan is a touch re-thought, it could be a winner.”

Champions, Sydney Festival, Carriageworks, Sydney, 2017

Performers: Sara Black, Kristina Chan, Cloé Fournier, Carlee Mellow, Sophia Ndaba, Rhiannon Newton, Katina Olsen, Marnie Palomares, Melanie Palomares, Kathryn Puie, Miranda Wheen

Photo: Heidrun Löhr